By Swann Collins, investor, writer and consultant in international affairs – Eurasia Business News. November 23, 2024. Article no 1318.

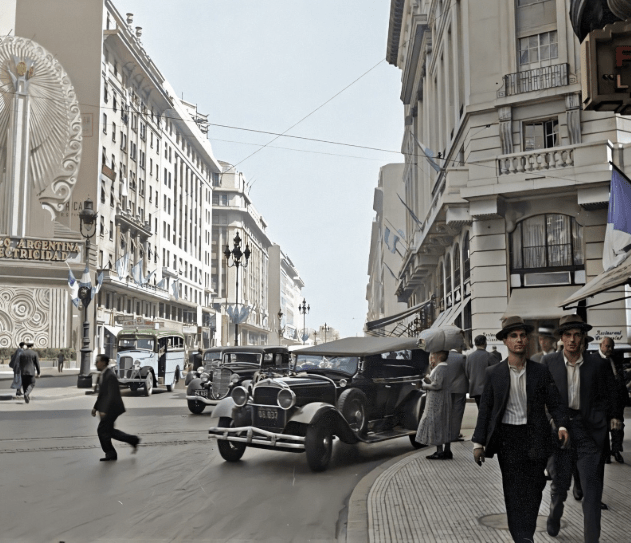

Picture : Streets of Buenos Aires, 1920’s, National Archives of Argentina.

Argentina was once considered one of the wealthiest countries in the world, particularly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By 1913, Argentina’s per capita income was comparable to that of Western Europe, and it ranked among the top ten wealthiest nations globally. This economic prosperity was largely driven by its vast agricultural resources, particularly in cattle and grain production and its large seacoast opened to international trade which allowed for significant export growth and attracted considerable foreign investment and immigration.

Economic Growth and Wealth of Argentina

Late 19th Century Boom: Between 1860 and 1930, Argentina experienced remarkable economic growth, outpacing many countries, including Canada and Australia, in terms of population and income. The country became a “super-exporter,” benefiting from low trade costs and an open economic system that facilitated trade with Europe and the Americas.

Argentina was a land of opportunities for ambitious people. The Greek magnate Aristotle Onassis moved to Buenos Aires in 1923 and established himself as a successful tobacco trader and later a shipping owner during the World War II (1939-1945).

Picture : Trade port Buenos Aires, 1930’s, National Archives of Argentina.

High Per Capita Income : In the early 20th century, Argentina’s per capita GDP was nearly equal to that of the United States, with real wages approaching those in Britain. The phrase “riche comme un Argentin” (rich as an Argentine) was used in France to describe extreme wealth during this period.

Picture : Streets of Buenos Aires, 1920’s, National Archives of Argentina.

In the early 20th century, Argentina was one of the wealthiest nations globally, benefiting from vast agricultural resources and a liberal trade environment. However, this prosperity began to erode as socialist ideologies took root in the political landscape.

Picture : Streets of Buenos Aires, 1920’s, National Archives of Argentina.

How instability and socialism broke the Argentina’s economy

However, this prosperity began to wane after the 1930s due to a combination of political instability, economic mismanagement, and global events such as the Great Depression of 1929. The rise of protectionist policies and autarky during this time led to a significant decline in economic performance.

However, Argentina’s economic decline throughout the 20th century can be significantly attributed to socialist policies, particularly those implemented during the era of Juan Perón and subsequent governments.

The Rise of Socialism

The shift towards socialism began in earnest with the populist and army lieutenant-general Juan Perón’s rise to power in 1946. His administration embraced populist and socialist policies aimed at wealth redistribution and state control over key industries.

Picture : President Perón at his 1946 inaugural parade in Buenos Aires.

Peronism was variously described as a variant of nationalist socialism, paternalistic socialism, non-Marxist socialism and Catholic socialism. Perón created a planned and heavily regulated economy, with “a massive public sector of nationalized industries and social services” that was “redistributive in nature” and prioritized workers’ benefits and the empowerment of trade unions.

These reforms enshrined government-backed favoritism of dominant interest groups and encouraged widespread rent-seeking instead of productive economic activity.

Nationalization of major sectors such as railroads, airlines, and energy

The nationalization of industries in Argentina, particularly during the mid-20th century under Juan Perón, had profound long-term effects on the country’s economy. These policies aimed to redistribute wealth and promote social welfare but ultimately led to significant economic decline. These policies also fueled corruption and nepotism, since nationalization benefited those who were close to the ruling groups. Gains of nationalized companies were not invested but rather distributed with populist aims.

Nationalized industries, including railroads, airlines, and utilities, became bloated and inefficient. The management of these state-owned enterprises (SOEs) often prioritized political loyalty over competence, leading to poor service and outdated infrastructure. For instance, the nationalized railroads operated at a loss of millions daily due to overstaffing and lack of investment in maintenance.

The concentration of power in state-run industries fostered environments ripe for corruption. Bureaucratic inefficiencies led to rampant mismanagement, further draining resources from the economy.

Increased Fiscal Deficits

State-owned enterprises required continuous government subsidies to operate, contributing significantly to fiscal deficits. By the mid-1980s, losses from these enterprises absorbed a substantial portion of Argentina’s GDP, exacerbating the country’s debt crisis. The reliance on state-owned companies for essential services created a cycle of financial dependence on government support.

Juan Perón implemented a range of social programs designed to improve the living standards of the working class (labor laws, healthcare, housing projects). Perón’s economic strategy included a Five-Year Plan that focused on industrial growth and self-sufficiency. He aimed to stimulate domestic production through import substitution policies, which sought to reduce reliance on foreign goods by promoting local industries.

This approach was supported by significant wage increases that raised workers’ real wages by approximately 35% from 1945 to 1949. By 1955, about 42% of Argentine workers were unionized, which was among the highest rates in Latin America.

Price controls and regulations stifled competition and innovation. These policies made Argentina less attractive for foreign investors and slowly destroyed the strenghts of the country that ranked it amid the ten richest nations in 1913.

Initially, these socialist policies garnered significant support among the working class but ultimately led to widespread economic inefficiencies. The state’s control over production and pricing disrupted market dynamics, resulting in decreased productivity, chronic inflation and less investments.

Following Juan Perón’s rise to power, populist-style income and wealth redistribution policies and further erosion of the system of checks and balances proved detrimental to Argentina’s institutional development and its path of long-run growth.

Economic Consequences

The consequences of these socialist policies started in 1946 were severe:

Chronic Inflation: The government frequently resorted to printing money to finance social programs and cover fiscal deficits, leading to hyperinflation that rendered savings worthless.

By the end of the first term of Juan Peron, inflation had already begun to rise significantly—accumulating to an inflation rate of 297.57% from 1946 to 1951 due to expansive monetary policies and government spending without corresponding revenue increases.

Argentina faced hyperinflation in the 1980s, when the price of goods and services increased by more than 50% per month. Although inflation has come down, it still exceeded 200% in 2023. After the election of the libertarian president Javier Milei and the implementation of his reforms, inflation has slowed to 2.7% in October, the lowest level in three years.

Economic Isolationism: Protectionist policies of the Peronist state limited international trade, reducing foreign investment and stifling economic growth. The government imposed high tariffs on imports while taxing exports heavily. This only fueled further inflation.

Public Sector Deficits: State-owned enterprises often operated at a loss, contributing to significant fiscal deficits that further fueled inflationary pressures.

Despite attempts at reform during the 1990s under President Carlos Menem, which included privatization and market liberalization, the foundational issues stemming from decades of socialist governance persisted. Menem’s reforms were often criticized for being insufficiently aggressive in dismantling the entrenched socialist framework.

By the late 20th century, Argentina’s economic situation deteriorated further, characterized by high inflation rates and increasing poverty levels.

Read also : Gold : Build Your Wealth and Freedom

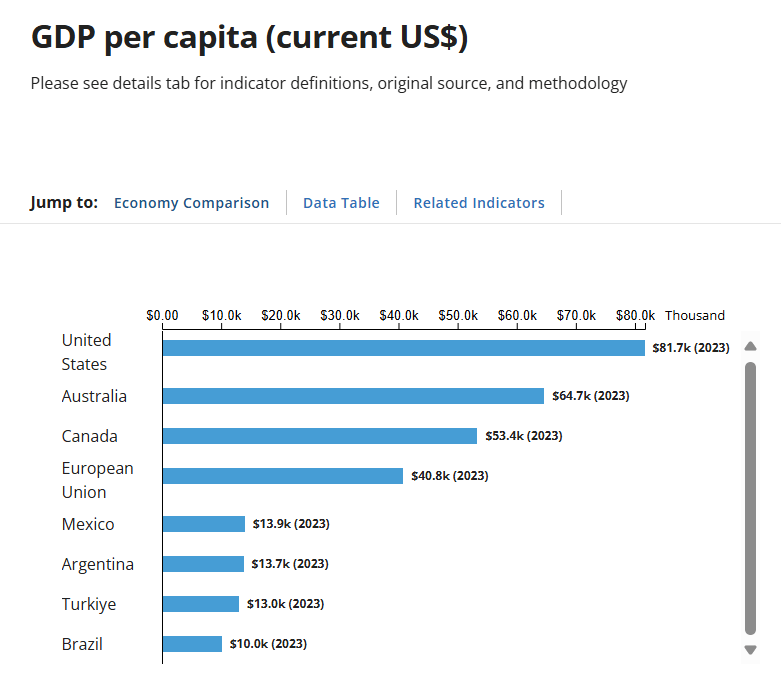

Today, the Argentina’s per capita income is comparable to that of Turkey or Mexico, a stark contrast to its earlier status as a wealthy nation.

In summary, Argentina was indeed once a rich country with significant economic growth driven by agriculture, industry and favorable conditions for trade. European immigrants fueled innovation and business work ethics. However, political factors over the 20th century have led to its decline from those heights : socialism, peronism, corruption, nepotism.

In the early 1990s, the government reined in inflation by making the peso equal in value to the U.S. dollar and privatized numerous state-run companies using part of the proceeds to reduce the national debt.

The 1998-2002 crisis was precipitated by Argentina’s adherence to a fixed exchange rate policy established in the 1990s, which pegged the Argentine peso to the U.S. dollar. This policy, initially seen as stabilizing, became unsustainable as external shocks—such as the Russian financial crisis in 1998 and Brazil’s devaluation in 1999—exposed Argentina’s vulnerabilities.

The economy entered a recession in 1999, which lasted until 2002. During this period, GDP contracted by about 28%, leading to widespread unemployment and poverty.

In addition, by the late 1990s, Argentina had accumulated significant public debt, reaching approximately $95 billion. This debt burden became increasingly unmanageable as economic growth stalled and tax revenues declined.

Unemployment soared to over 20%, and poverty rates escalated dramatically, with estimates indicating that around 57% of Argentines lived below the poverty line by 2002. This was particularly devastating for children, with about 70% living in poverty at the peak of the crisis.

During the 2010s, Argentina’s economy experienced a mix of growth, challenges, and significant volatility. The decade began with a strong recovery from the global financial crisis but faced various economic difficulties later on, including high inflation, currency devaluation, and political instability.

Starting in 2012, Argentina’s economy began to slow down due to several factors, including reduced demand from key trading partners like Brazil and Europe. Growth averaged only 1.3% from 2012 to 2014, with significant inflationary pressures emerging.

Inflation became a persistent issue throughout the decade, often exceeding 25% annually. The government struggled to control prices despite implementing various measures such as price controls and currency restrictions.

The COVID-19 pandemic severely affected Argentina’s economy, leading to a GDP contraction of 9.9% in 2020. Lockdowns and restrictions resulted in a significant drop in economic activity, with unemployment rates soaring to around 14%.

Inflation surged dramatically, reaching 50% by the end of 2021 and 200% by the end of 2023. The government struggled to control prices despite implementing various measures, including price controls and negotiations with businesses.

In January 2024, Argentina’s poverty rate reached 57.4%, the highest poverty rate in the country since 2004.

The change with Javier Milei

The election of Javier Milei in December 2023 marked a significant turning point for Argentina, as he implemented a series of radical economic reforms aimed at addressing the country’s longstanding economic issues, particularly hyperinflation and fiscal deficits.

In september 2024, for the first time in over a decade, Argentina achieved a fiscal surplus over nine months in a row, indicating a significant turnaround from previous years of deficit spending. This budget surplus was largely attributed to severe austerity measures, including substantial cuts in government spending and subsidies.

Libertarian President Javier Milei, who campaigned in 2023 on building budget surpluses and recovering the purchasing power of the currency, has been able to achieve his aims by enacting abrupt and often draconian austerity measures as soon as he took office in December 2023. Milei opposes socialist and communist ideologies, which he regards as oppressive systems that generate poverty, corruption and hunger.

Now, after 11 months, he seems he is winning his bet, the Argentinian economy showing signs of strong recovery.

Argentina recorded a primary surplus of approximately 1.7% of GDP and a financial surplus of nearly 0.4% of GDP during the first nine months of 2024. Specifically, in September alone, the primary surplus reached 816,477 million pesos (around $837 million), while the financial surplus was 466,631 million pesos (approximately $478 million) after accounting for interest payments on public debt.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts an optimistic rebound, predicting a 5% growth in 2025, following a contraction of 3.8% in 2024. The IMF’s projections suggest that while inflation will remain high, there are signs of gradual economic recovery.

BBVA Research presents an even more optimistic outlook, estimating a 6% rebound in GDP for 2025, driven by increased investment, exports, and private consumption. They highlight signs of recovery in Q3 2024 as real wages begin to rise.

Thanks to the disruptive policy of Javier Milei, Argentina’s inflation slowed to 2.7% in October, the lowest level in three years in a win for the libertarian government of President Javier Milei who came to power almost a year ago promising to pull Argentina out of a dire economic crisis. When he took office in December 2023, monthly inflation surged to 25%.

However, Milei’s administration has faced political challenges due to its minority status in Congress. This has limited the scope of some reforms and created potential gridlock ahead of the crucial midterm elections in 2025.

Our community already has nearly 145,000 readers!

Subscribe to our Telegram channel

Follow us on Telegram, Facebook and Twitter

© Copyright 2024 – Eurasia Business News. Article no. 1316.